No-one is interested in someone dancing about vainly (Sophie, Scene 4). What, then, makes dance worthwhile? Why would I spend my life dancing and teaching dance if it was only in vain?

In the last week of July, I worked on Helen Caddick‘s opera ‘Sophie’ with choreographer Kamala Devam and director Lucy Bradley. Helen’s score is inspired by the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943), a multidisciplinary craftswoman, educator and creative who also danced. Her dance practice, however, is far less documented than any of her other artistic achievements.

In a review of the Sophie Taeuber-Arp exhibition presented at Tate Modern, writer Katie Hagan of Dance Art Journal reflects on the lack of documentation of Taeuber-Arp’s dancing. Indeed, dance was the only missing piece in a carefully curated selection where paintings, textiles, sketches, sculptures, marionettes, furniture and evidence of works of architecture all found their place. Why could dance not claim one? Was it too difficult to insert dance in the exhibition rooms? I don’t believe it. Recently, many installations and events have placed dance in galleries and interrogated its place there. Contemporary artists and choreographers like Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker have been filling white cubes with performative interventions. But in this instance, there was no space for dance. Just like Katie, ‘I would have liked it to feature a little more explicitly in the exhibition’.

The retrospective only featured two traces of dance. The first one, tucked in a corner, was a black and white photograph of Sophie dancing. The second, screened outside the exhibition rooms, was a film of her marionettes in motion. Since both of these pieces were two-dimensional documents from the past, I wondered why no performative happening had been scheduled within the exhibition time frame, to bring some life inside the still, three-dimensional gallery space. Weeks after having drafted this blog post, I found out that a live dance performance would take place as part of Tate Modern Lates and feature a dancing response to the retrospective by my colleague Gerrard Martin. In my experience of the exhibition, however, dance shone by its absence. It felt relegated to the margins of the main event, pushed at the bottom of an implicit hierarchy of art forms. Yet, as Hagan’s review suggests it, the lack of documentation of Taeuber-Arp’s dance practice could also be seen as a strength, with the potential to prompt questions and creative interpretations of the artist’s work. This made the research and development of choreographic material for ‘Sophie’ pleasantly open-ended and very stimulating.

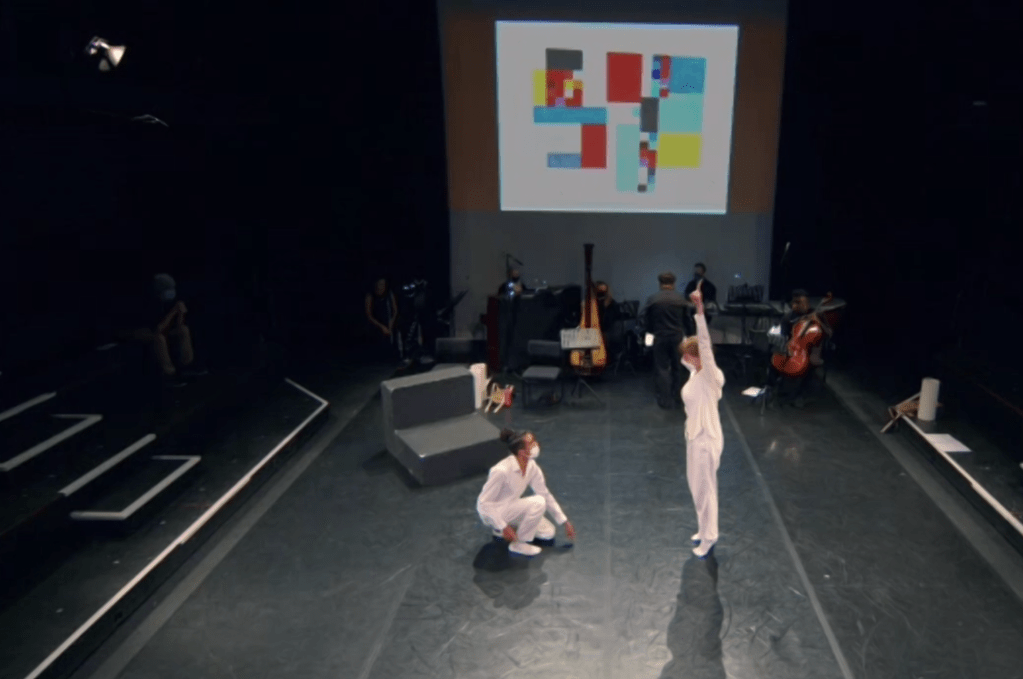

Geometric patterns found in Taeuber-Arp’s compositions provided starting points for choreographic explorations such as ‘Vertical Horizontal’ – a fast-paced dance interlude inserted in Helen’s opera and expertly conducted by Chris Hopkins.

This scene made me appreciate that, instead of claiming the lead role, dance could work wonderfully well as an interlude or fantasy emerging between the chapters of Sophie’s captivating story. My duet partner Aaron Baksh and I had to push ourselves to keep up with this section’s fast tempo. To give you a metaphorical interpretation of our actions, I would say that we were hopping over the hard reality of a creative career, falling from frustration and rising from the ground again to run after rare artistic opportunities.

The countless changes of levels in our duet may well have evoked emotional ups and downs in Sophie’s life. But the speed at which we danced suggested an attempt to escape both defeats and victories in the rollercoaster of a creative career.

Lending her voice to the role of Sophie, Elizabeth Lynch conveyed all of these emotions equally well, with a charismatic presence and resonance that dance movements alone would probably have struggled to achieve. While Sophie and Jean Arp admired nature, in which every from has arisen out of a deep necessity (Sophie, Scene 2), a dance like ‘Vertical Horizontal’ could be read as a striking example of unnecessary lines, forms and movements. Unlike actions performed in everyday life, sports, or even theatrical performances, dance movements aren’t goal-oriented. They can exist without purpose, story, target or task. In this scene, the forms and lines of energy we shaped across space and time were drawn for their own sake. Following the Dadaists’ invitation to see what you make and the principle that everyone can think whatever they want (Sophie, Scene 4), Kamala, Aaron and I used Laban’s analysis of human movement as a combination of actions, body parts, dynamics, space and relationships, to create our own score and give the audience freedom of reading. The white costumes we wore offered them a canvas for imaginative interpretations.

So what could they possibly interpret? In her essay ‘Dada Dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction‘, Nell Andrew analyses ‘the dancing body as a medium for Dada’. She argues that the way Taeuber used her body ‘merge[d] the viscerally felt chaos of her time to the order of form’.

This vision of dance as both a structured form and a felt experience strongly resonates with me. As suggested by Andrew, putting a dancing body’s presence in relation to ‘its disintegration or absence’ translates ‘Dada’s hope for an art free of institutionalized meaning’. Andrew wonders if Taeuber’s abstract and calculated dance movements might have presented ‘the possibility of new responses, actions, and gestures that have been freed from fixed meaning’. This freedom was at play in a scene inspired by the Cabaret Voltaire. The Dada dance we set to this scene depicted what the writer called ‘an anarchist claim to freedom within existing modes of art making’: we combined restrictions in the form (such as wearing a tall Dada hat) with bursts of individual and idiosyncratic expressions.

In this spirit, I performed spins and swirls that communicated a form of frenzy without strictly making sense. This was a fair response to Hugo Ball’s sound poem, powerfully recited by Neil Balfour. Transported by his voice and gone past the initial dizziness, I ended up Dancing the Dada way and finding it a liberating experience. My Dada dance movements didn’t leave a trace. They didn’t produce any object to exhibit or sell. They may have been recorded, but who knows? Our current video archives may not last forever. All I had and shared with our audience was an intangible and exhilarating chance: the power to re-imagine and embody what a bold dance artist had discovered 105 years ago. A wind of freedom in a terrifying world.

Like Andrew, I see the photograph of Taeuber’s dance performance as a way of giving ‘Dada’s static art its most physical presence and realness, while also performing its drive toward disintegration and death’. I tremendously enjoyed using my physical presence to inhabit a small part of art history. After months of online dance classes and rehearsals, contributing to the creation of choreographic material for ‘Sophie’ in a shared space with collaborators was refreshingly real. Yet, the research and development process only brought us together for 5 days, at the end of which we performed our work in progress at Tête à Tête Opera Festival. As I write this post, the creative team has disintegrated and drifted off to other projects. We hope to meet again and continue staging ‘Sophie’, but nothing can be taken for granted – funding the arts and producing performances is largely a lottery.

Despite this uncertainty, our brief and intense creative process left me elated and determined to echo of Sophie’s own words: I resolve to forge ahead in my quest to be an artist (Sophie, Scene 2). My own quest thrives in collaborative endeavours. So I will go where dance marries music, is featured in film, makes visual art vibrate and design dazzle. Sometimes, I might also smile at the absurdity of practicing my discipline alone. Perhaps Dancing the Dada way is the art of acknowledging this absurdity, and the belief that dance isn’t vain when connected to other art forms.

References

Andrew, N. (2014) ‘Dada Dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction’ in Art Journal 73:1 (Online). Available from: http://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=4680 (Accessed: 10 August 2021)

Caddick, H. (2021) Sophie – Libretto extracts. Available from: https://www.tete-a-tete.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Sophie-sharing-libretto-extracts.pdf (Accessed: 10 August 2021)

Hagan, K. (2021) ‘SOPHIE TAEUBER-ARP EXHIBITION – TATE MODERN – REVIEW’ in Dance Art Journal (Online). Available from: https://danceartjournal.com/2021/07/27/sophie-taeuber-arp-exhibition-tate-modern-review/ (Accessed: 3 September 2021)

Photo credits

Header image by Helen Caddick, rehearsal photos by Lucy Bradley, screenshots of performance footage and feet picture by Yanaëlle Thiran.